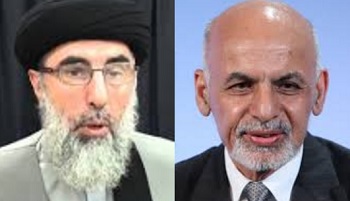

Ghani-Hekmatyar Peace Deal Smacks of Desperation

Michael Hughes

October 1, 2016

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani on September 29 consummated a peace agreement with notorious warlord and internationally-designated terrorist Gulbidden Hekmatyar, who is renowned for being the only prime minister in history to bomb his own nation’s capital. The immediate and obvious question is: Why? Why strike a peace deal with an exiled war criminal who wields very little influence inside present day Afghanistan? What is the rationale for welcoming Hekmatyar back to Afghanistan when true justice calls for dragging him in front of The Hague?

Perhaps Afghan officials – and the United States for that matter – are so desperate to entice the Taliban to the negotiating table they are willing to make Hekmatyar a case study in reconciliation, of sorts. The message being: If the Afghan government can strike a deal with this abomination – it can strike a deal with anyone.

For those unfamiliar with who were are dealing with here, Hekmatyar’s greatest hits include skinning captives alive during the Soviet-Afghan war, throwing acid on women for exposing anything but their eyes, and slaughtering his own people in a bloody civil war in the 1990s. The former amigo of Osama bin Laden has even been likened to the Devil himself.

“In the Soviet-Afghan war’s early stages, I spent time with Hekmatyar. A saturnine, Satanic fundamentalist with a fondness for Gucci shoes,” war correspondent Anthony Paul wrote in 2003. “[H]e made the phrase ‘Muslim extremist’ seem inadequate.”

And in the West, of course, he epitomizes everything that was so wrong about the U.S. strategy to fund, arm and train the mujahideen “freedom fighters” of yore.

Despite this track record, the 25-point peace agreement will give Hekmatyar absolute immunity for all of these previous atrocities. What is truly startling is that the U.S. embassy in Kabul, the UN and EU have all “welcomed” this development.

Not to mention, Afghan officials have received assurances that Hekmatyar will be delisted from the various terrorist lists he has earned a spot on, thanks in large part to President Ghani’s lobbying efforts. To say this fosters a “culture of impunity” would be an understatement.

The Faustian bargain with Hekmatyar for peace at all costs signals how precarious the security and political situation truly is in Afghanistan. The Taliban are arguably in a stronger position militarily than at any time since they were toppled in 2001. Kabul is dealing with a political crisis that has no end in sight and a government struggling to appear legitimate in the eyes of most Afghans.

Yet there seems little indication that the downside of such an agreement has been heavily weighed. What if it backfires? Hekmatyar’s ambition for power seems unquenchable. Could he be a disruptive force?

Even more unexamined is the possibility that he is a Trojan horse for the Pakistanis – Hekmatyar being the ISI (and CIA’s) favorite son during the jihad against the Soviet Union. For starters, Pakistan seemed conspicuously upbeat about Ghani cementing the accord with the warlord.

“Politically negotiated settlement through an Afghan-owned and Afghan-led peace process is the most viable option for bringing lasting peace and stability to Afghanistan,” Pakistan’s foreign ministry said in a statement.

The Pakistanis claim they are “encouraged” because it is their “earnest hope” that the agreement with Hekmatyar paves the way for similar accords between Kabul and other Afghan insurgent groups “for achieving durable peace in Afghanistan.”

To be fair, former Indian diplomat M.K. Bhadrakumar has actually given this scenario some deep thought.

“For Pakistan, the prime consideration would be that Hekmatyar has a fierce reputation for being ‘anti-Indian’,” Bhadrakumar writes in Asia Times. “He was unique among Mujahideen groups to explicitly threaten to fuel the insurgency in Kashmir.”

Hekmatyar can guarantee on Islamabad’s behalf, Bhadrakumar further argues, that “there will be no nexus possible between Delhi and Kabul in any future political dispensation in Afghanistan.”

New Delhi likely sits and looks upon the situation with befuddlement, or even feeling they have been duped by the United States. Over the past month or so it seemed as if India had momentum in the new Great Game.

“How will that affect the U.S. stance apropos India-Pakistan tensions or the upheaval in the Indian part of Kashmir? India has reason to feel worried,” Bhadrakumar claims.

Washington punished its wayward ally Pakistan for Islamabad’s recalcitrance in rooting out the Haqqanis by aligning with New Delhi on a range of economic and security initiatives. After all, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry stood on Indian soil at the end of August and chastised Pakistan for its pro-terror policies while Pentagon chief Ashton Carter struck a base-sharing arrangement with his Indian counterpart.

Now the pendulum might be swinging the other way as the U.S.-Pakistani mujahideen leader returns to play a crucial role in the never-ending geopolitical chess match. Stay tuned to see if the Haqqani Network is the next group to test the waters of reconciliation.