Intra-Afghan Talks May Be Doomed by Differences Over Future Political System

Michael Hughes

July 1, 2019

Members of the Taliban and Afghan government are supposedly set to begin negotiations within the next two weeks but it is hard to imagine how they will overcome what appear to be irreconcilable differences over the very nature and structure of the country’s future political system.

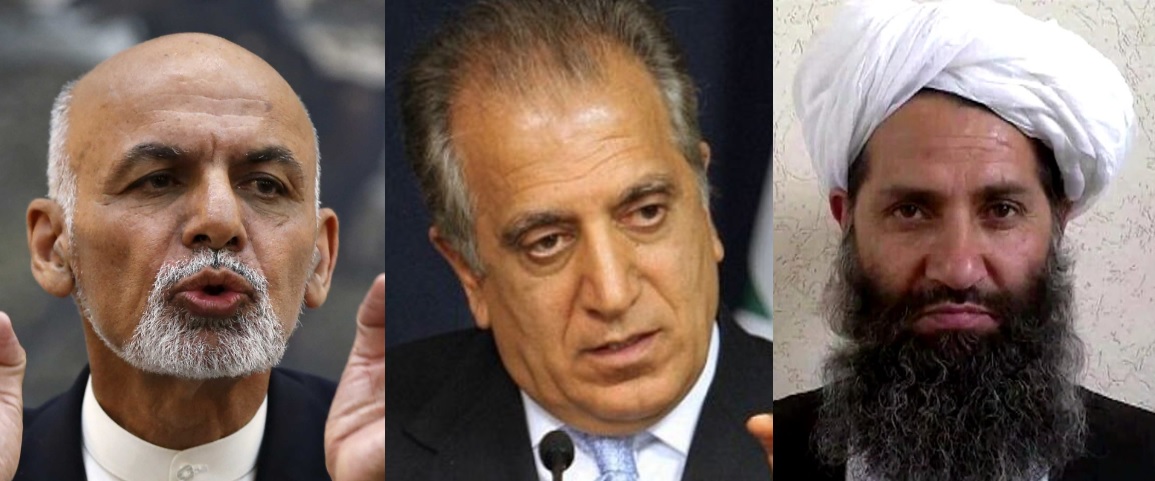

Taliban officials have openly stated they refuse to recognize the results of the September 28 presidential election despite Washington’s claims that the insurgents have agreed to negotiate with Kabul. U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad, who is leading the U.S. side of talks with the Taliban, said engaging the Afghan government is one of the conditions of any deal to end the war.

“A comprehensive peace agreement is made up of four inter-connected parts: counter-terrorism assurances, troop withdrawal, intra-Afghan negotiations that lead to a political settlement; and a comprehensive & permanent ceasefire. This is a framework which the Taliban accept,” Khalilzad said in a Twitter post on June 18.

Unfortunately, the Taliban’s recent deeds and words have shown that they are far from ready to reconcile with Kabul. On Saturday, June 29, shortly after the seventh round of talks between U.S. and Taliban negotiators kicked off in Doha, at least eight people were killed, including employees of the Independent Election Commission, during an insurgent attack in Kandahar.

Moreover, the Taliban in a statement on June 24 warned members of Afghan media to either halt broadcasting negative ads about the insurgent group or they will become “military targets.”

Hence, the Taliban oppose both the very nature of Western-style representative government which derives its legitimacy from the ballot box and the values associated with this type of system.

The Afghanistan Analysts Network’s Thomas Ruttig, in an excellent analytical piece, explains that the Taliban want to see a shura-ye hal o aqd – an Islamic form of representation through elite selection as opposed to popular vote. Ruttig, citing a former Taliban minister currently involved in the talks, said the insurgents prefer that handpicked figures such as the ulama choose the country’s leaders.

“The presidential republic system… reserves one vote for both a layman and a well-educated person. Obviously, the laymen cannot make a perfect choice,” the former Taliban minister is quoted as saying in a New York University study.

However, the same minister also outlined a potential compromise scenario for a post-withdrawal state. The “middle way,” the minister suggested, would encompass a three-tier system based on ordinary people electing district councils which, in turn, elect a parliament which then elect the country’s leader.

Meanwhile, there are concerns about whether or not the ultimate system adopted is one that actually, for once, reflects the will of the Afghan people. Although it is one thing to propose something along tribal lines, for example, some fear the Taliban may have something in mind that is more Wahhabi-based and inimical to Afghan tradition.

Not to mention the obvious concerns over whether or not the Taliban are even capable of tolerating gains made in areas such as women’s rights and other protections of civil liberties.

The U.S. and Western powers, to be sure, imposed on the Afghans this Occidental ballot-box system after rigging the traditional Jirga to anoint a Washington-backed puppet in 2003. That said, as Ruttig pointed out, the participation of voters has still been high – with many often braving security threats to cast ballots, which suggests that elections are important to Afghans. Despite this, the Taliban have exhibited no desire or willingness to accommodate such a process.

“In contrast to the government, the Taliban have never put themselves to any form of vote; their rule in areas they control seems rather to be based on a combination of military power and coercion and some local consent,” Rutting argued.

The mysterious component of the U.S.-Taliban agreement is regarding the role the insurgents will play in the Afghan political structure. Washington, one would think, should have no say in what this future structure would look like. There is some irony here that the United States could be paving the way for a possible regression from the modern political system – which Washington helped institute – towards a system that resembles an Islamic state.

There is also something incoherent about the two political processes currently underway. On the one hand political reconciliation with one group of stakeholders and an election process that represents all factions within Afghanistan’s ethno-sectarian mosaic.

The insurgents are certainly willing to wage war for centuries if foreign occupiers do not withdraw from Afghan soil. Yet even if the insurgents reach a deal with Washington and U.S. forces exit, Afghanistan is likely to never see peace unless – by some miracle – the Taliban wake up one day suddenly ready to embrace a political system based on the tenets of modern liberalism.